For more than twenty-five years Denise Chávez and others put on the Border Book Festival in first Mesilla, New Mexico, then Las Cruces. She served as executive director.

She received her bachelor's degree from New Mexico State University and master's in theatre from Trinity University, whose program was housed at the Dallas Theatre Center. While in college she began writing dramatic works. Later she entered the MFA program at the University of New Mexico and earned a degree in creative writing under the direction of mentors Rudolfo Anaya and Tony Hillerman.

In 1986 Chávez published her first collection of short stories, The Last of the Menu Girls (Arte Publico; reprint, Vintage, 2004). She has received various awards, including the American Book Award, the Premio Aztlán Literary Prize, the Mesilla Valley Author of the Year Award, and the 2003 Hispanic Heritage Award for Literature. Chávez taught at New Mexico State University for various years, eventually moving on to create the Border Book Festival.

In March Chávez and her husband, Daniel Zolinsky, announced the end of the Festival’s run, and their revised focus on selling books on Abebooks (abebooks.com) and on developing Museo de La Gente, a cultural resource center that serves to preserve, document, and celebrate the story of the Borderlands community in the southwestern United States and northern Mexico.

Author photo by Daniel Zolinsky

5.3.2015 Denise Chávez: Leer Es Vivir / To Live Is to Read

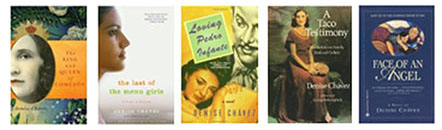

Internationally prize-winning author Borderlands Book Festival founder Denise Chávez is the author of The Last of the Menu Girls, Face of an Angel, Loving Pedro Infante, and A Taco Testimony: Meditations on Family, Food, and Culture. Lone Star Literary Life caught up with her by email to talk about writing, her shared culture of Texas and New Mexico, and her newest book, The King and Queen of Comezón (University of Oklahoma Press, 2014).

LONE STAR LISTENS: I have seen you at readings on more than one occasion, so let me just say, I could sit and listen to you all day. You actually started out as an actress, didn’t you? How did that background affect your writing?

Theatre was and is my life. I refer to myself as a “performance writer.” At my first major reading, I read “in my style” and when I got off stage, Rudolfo Anaya, author of Bless Me Ultima, asked me what I’d done. It didn’t seem unusual; really, I was just, acting my lines. Who better than me? If I want to change my lines I can at any time. I always ask people not to read along when I am reading a section of something I’ve written. I’m likely to change something. There is danger in this, though. It’s sometimes hard to go back. Every writer should try memorizing some of their work and performing it. There’s much to be learned about rhythm, color, authenticity of voice, truth. Learning my own lines for a character who has Alzheimer’s in a play I wrote called Novena Narrativa, was incredibly hard. Much like memorizing Beckett or Ionesco, which I have done as well. It’s a good exercise in which one has to find the logic or movement in the illogical.

I always tell writers to take an acting class, to study speech and movement, and to become the best performers of their words that they can become. It’s important.

So you’ve divided a lot of your time between Texas and New Mexico when you were growing up, and when you were pursuing your academic and theatrical aspirations. How are Texas and New Mexico different? And yes, we have all day.

Texas is my mother’s country and New Mexico my father’s world. I have always navigated the magic and mystery of both universes. They are pivotal realities to me. To write about their similarities and differences would take a book. And I am doing that now. I am working on a book called Río Grande family, about my mother’s family in Far West Texas.

This includes the Rede and Faver families of the Trans-Pecos area, including the cities of El Polvo (later renamed Redford), Presidio, Fort Davis, and Marfa, as well as Ojinaga, Delicias, and Chihuahua, México.

The book includes a creative and analogous cross current of writing and art, what I call "imprinting.” The use of theatrical and creative writing techniques are part of who I am as a performance writer, and these aspects will contribute to ancestral monologues, dialogues, and a series of Cuentitos—little stories from the Voices of my Ancestral Kin—as well as the inclusion of old photographs and writing from various members of my family, including my mother Delfina’s poems and the narratives of other family members.

One great river, the Río Grande. Roots in México, Texas, and New Mexico. Each of these places is a sacred arc of the setting out and taking hold, each a homeland.

How did you choose between acting and writing?

At one point, in my mid- to late twenties, I was writing mostly plays. I could have gone on to become a full-time playwright. And while I consider myself an actor, the thought of a lifetime of rehearsal in darkened theatres was a hard thing to ponder. Also, I knew I had to move to New York or Los Angeles if I was to become a serious actor. I didn’t want to do that. I remember a playwright in Albuquerque who asked me, “Why do you always write about New Mexico?” He could as easily have asked me, “Why do you always write about Texas?” I write about my world, the world I know, love and am grounded in. I couldn’t write about New York and I knew it.

I still have plays in me, as I have poems and stories. For now, and at this time, I do go back and forth between genres. But for some reason, there is nothing quite so satisfying in the long run as a “long run.” I love novels and the heft and thickness of a good long story. Read Dostoyevsky or Thomas Mann and revel in greatness.

I haven’t really left my acting behind. It is with me daily and I thank all my mentors and teachers who taught me the craft. I studied playwriting at the University of Houston with Edward Albee, have been mentored and studied with Megan Terry, José Quintero, Takis Muzenidis (a director from Greece), Leo Lavandero (a Puerto Rican director) Hershel Zohn (a Russian director) and many others, including the great American director Paul Baker, who was a genius. I have learned the power of art from all my mentors and I am deeply grateful.

What was your first break as a writer? How did it change your life? Who helped you along the way?

I've had so many breaks they are legion. I was lucky to go to an all girls’ Catholic school, Madonna High School. There were twelve of us in our graduating class and we called ourselves “The Apostelletes.” I was writing plays as a freshman in high school. Not knowing how to write a play, I wrote them. No one ever held me back. During Holy Week, I read the Passion at Mass (a good acting gig) and was often called upon to recite. The skinniest girl in the class (me)—played Santa Claus for the Christmas play. All seemed possible in writing and art.

My mother was always encouraging even though she once said “What, another rehearsal?” She used to pick me up at one or two in the morning from the university theatre when Mr. Zohn kept us long as we should have called it quits. Mother also gave me my first thesaurus at age ten. I still use it and treasure it. My mother, Delfina Rede Faver Chávez, was a cultured woman and would take my sisters and [me] to art movies, to the symphony, and to art exhibits. She loved music, theatre, life. She was my first and will always be my best fan.

I could tell of the check for fifteen dollars for my first playwriting prize as a freshman in college (I probably have a copy of the check somewhere still) or the $500 that came to me from an anonymous donor when I was down and out in Santa Fe. I have been saved by blessing more than a few times. And my tale is still about the early days of my work! My life is one of miracle and it has only gotten more miraculous. And miracle in my life has nothing to do with money or fame!

I have read that at age twenty-four, when things were coalescing for you as a writer, you went outside and declared to the universe that you were a writer, and later that you had your creative writing students do the same thing as a part of their process. Why is the ritual important?

This story is true. I knew I had to place my prayer at the deepest core of belief and at a place of spirit. I wrote my first story at age eight. I knew I wanted to be a writer at age ten. When I was in my early twenties, I just didn’t know how I was going to work it. I knew I had to “postulate provision.” And that meant putting myself in alignment, or better said, “on the river of possibility.” I didn’t know how I was going to make a living, still don’t. . .but I had to be ready to act when the opportunity for action came along. This Declaration to the Universe is crucial to all of us. So, the young woman that I was, laying on the roof of our home, declared herself, to a life of work and service. I had a — a gift, and my manda — my promise — was to serve the word, my art, my craft, my deepest being. Doing this allowed me to never falter and to keep hope in nearly hopeless times. This is another book!

How has writing changed since you started? What do you think about all of the different paths to publishing that are available now?

I had a great opportunity to be published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, and by other New York houses. I was young and the publishing industry is always looking for “shooting stars” — for young writers to make the wild literary arc and become great and instant successes. Sandra Cisneros was a huge success, and many other Latino writers found their work being appreciated and valued. Now we have fewer Latino or multicultural writers getting published. Read Poets & Writers magazine and see the dearth of writers giving workshops in Poland or even San Miguel de Allende. It’s the same names over and over. What’s wrong with this picture? I once wrote an essay called “Move over, Gerald Stern.” I have met Gerald Stern and love and appreciate him, so it’s not a personal thing. But it’s time for varied and multicultural writers to find favor with New York or other publishing houses, for their voices to be heard. Nowadays, alas, it’s a matter of sales figures. What’s the answer? For readers to read all sorts of books, to request those books in their bookstores, to get away from the corporatization of literature and to challenge the business of writing.

I probably would not self-publish at this time. Number one: I don’t have the money. Number two: I have seen so many self-published books languish on the shelves in our bookstore, Casa Camino Real. But on the other hand, it is a great for many writers, so if it works for you, adelante/forward!

I sell books online on Abebooks. Our store is Casa Camino Real and we have over 500 books listed at this point. We just started on our online store in October and I have sold books to Ecuador, Spain, and across the U.S. Our nonprofit organization, Museo de La Gente, an archival resource community center, sells books to make money for our ongoing project to preserve the legacy of story in our borderland community.

My work as a bookseller is a natural extension of my “play” as a child—making library cards for all my father’s books in his library and then notarizing them. My older sister, Faride, reminded me that doing that was probably illegal—but who was coming after a ten-year-old for notarizing her handmade library cards? I still have copies of those library cards in a frame at our bookstore to remind me where my love for books comes from.

When people come into our bookstore in Las Cruces, at 314 South Tornillo Street, I say, “This is the temple, and books are sacred.” I like what Borges says, “I have always imagined that Paradise will be a kind of library.” Maybe this is why I always loved the Shangri-La story, Lost Horizon, by James Hilton. It’s not that one wants to live forever, oh no, I just want more time to read and explore books!

Your latest book, The King and Queen of Comezón, has been described as a mystery love story with a befuddled patriarch and a less-than-tractable family. As an artist, what kind of portrait did you wish to paint with this book?

I wanted to write a book about longing and love on the U.S./México border and about what it means to be a good man or woman in an evil time. It’s a very southwestern, New Mexican and yes, Texas book. It’s about the unattainable “itch/comezón” of life. I hope readers will laugh a lot and cry some. I love my characters with all their flaws and sorrows. The writing of the book took over twenty years simply because I wasn’t mature enough for the work at hand.

Which Texas writers have influenced you, or whom do you admire?

I love all things Texan. My mother, Delfina, was a wonderful poet and writer. She was a powerful poet and translator as well. And she had very high standards as she was a Spanish teacher who studied thirteen summers at UNAM (La Universidad Autónoma) in México City. Diego Rivera was her art teacher, and she knew the luminaries of the day: Agustín Lara, the composer, Frida Kahlo, etc.

I grew up loving Mexican writers. Later I met many Texas border writers like Ricardo Sánchez, Abelardo Delgado, and Aristeo Brito (he’s a cousin from Presidio, Texas), and grew up with Benjamin Alire Sáenz, whose family is from Fort Davis. Ben is also a cousin.

Of course, I love Larry McMurtry and Elmer Kelton, who was great man. Who hasn’t enjoyed Molly Ivins and learned from historians Leon Metz and C. L Sonnichsen? There are powerful and moving books from Texans, including Rolando Hinojosa Smith, Carmen Tafolla, Tony Díaz, Norma Cantú, Gloria Anzaldúa, Ricardo Aguilar, Dagoberto Gilb, Estella Portillo Trambley, John Rechy, Sandra Cisneros, and many others. A master of fiction was the El Paso-born writer Arturo Islas. Tomás Rivera gave us Y No Se Lo Tragó La Tierra/And the Earth Did Not Swallow Him. It is a masterpiece of migrant farmworker lives. Texas has healed the world with its vision. And it continues to do so.

I am so proud to be a Texan/New Mexican and a New Mexican/Texan with roots in México. I grew up Catholic and have Sephardic Jewish roots in Delicias and Chihuahua, México, and am a Buddhist in my thinking. Go figure! Can’t we do and be it all?

What is your writing process like? Where do you go to write?

I write everywhere and in all places. I was just in Houston at Texas Southern for a conference called “All the World’s A Stage.” It was the first annual Undergraduate Research and Creative Activities Symposium directed by Dr. Elizabeth Brown-Guillory, who is the head of the honors program and a talented playwright. I had creative writing students from Texas and Nigeria and from across the US.

I wrote on the plane and in the workshop and in my room at the hotel. I often get up to write from 3:30 am to 7:30 am. I tell people, don’t languish! Get out of bed and write, no matter the time or place. Carry your journal with you and go to it! I write fast and hard and worked on a novel last November for the National Novel Writing Month online program. I didn’t finish my novel called "The Ghost of Esequiel Hernández," but I got deeply into it. The book is set in the Big Bend and has as a background the killing of the Redford, Texas, goat herder, eighteen-year-old Esequiel Hernández, who was mistaken by U.S. Marines as a drug runner. He was killed in 1997 in his backyard. It’s an American tragedy.

This year I am taking off the month to write another novel. If you want to invite me to Thanksgiving dinner, I’ll make time. The rest of the month I’ll be writing. The goal is 1,600 words a day. I met a writer at the Tucson Book Festival who has written eight first drafts with NaNoWriMo. It can be done!

Summer is just around the corner. Which books are in your beach bag?

I just finished the biography of Anthony Perkins, Split Image. It’s a sad story. I like biographies and am working my way through the biography Thomas Mann: Eros and Literature by Anthony Heilbut. Readers, you must read Doctor Faustus by Thomas Mann! At some point in each writer’s life we must face darkness.

I want to read more Latin American and Mexican authors. If you haven’t read Canek: History and Legend of A Mayan Hero by Ermilio Abreú Gómez, it’s a must-read. Right now I want to read the books my sister, Margo Chávez-Charles, has lent me and give them back to her, including People of the Book by Geraldine Brooks among others. I am also just starting From the Pass to the Pueblos, a wonderful history of the Camino Real by El Paso historian George D. Torok.

My reading is very ecletic!! I love books and now that I am a bookseller I am learning more about books and their authors. It is my great pleasure and honor to be the caretaker of many books and many collections. Our organization just got a donation of 5,000 pounds of books, 108 Banker’s Boxes of photography and art books from the private collection of Flagstaff photographer John Running. We will archive and preserve many of these books in our Museo de La Gente.

I have no beach bag, alas, my beach is this wonderful landscape of La Frontera, our borderland, which was once ocean. So, I guess you can say, my ocean is the border!!

Thank you for this great opportunity to share this world with your readers. Come and see me at Casa Camino Real and visit us at Abebooks.com.

Leer Es Vivir!

To Read Is to Live!

* * * * *

Praise for Denise Chávez’s work

“[Denise] Chávez’s voice is at once zany and knowing. She is la gran mitotera—a big troublemaker, stirring up rollicking mischief with wacky humor delivered in the lyrical tempo of Chicano slang.”

Publishers Weekly

“Chávez records the food, the hang-ups, the turn-ons and worldview of a thriving border culture. . . . [Her] spicy storytelling reminds us that women today, fictional and real, have . . . options. And while looking for idealized romantic love will never go out of style, finding it pretty much has.”

New York Times

“The King and Queen of Comezón is a work of pure, comic genius with just enough pathos thrown in to make us weep with gratitude. What Denise Chávez has done for the dusty border town of Comezón (or “Itch”)—for her entire beloved borderland, in fact—is akin to what William Faulkner created with Yoknapatawpha County or Toni Morrison with her native Ohio. The town may be small, but its unforgettable inhabitants live large, dream large, heart and soul.” —Cristina García, author of King of Cuba

“Denise Chávez is both king and queen of storytelling.” —Sandra Cisneros, author of The House on Mango Street

“The King and Queen of Comezón is rich, so full of raunch and beautiful flights of imagination, and humor, and descriptions of the human condition. Above all else, this book reeks of a deep love for humanity. The writing soars. Denise Chávez has written a classic for our age.” —John Nichols, author of The Milagro Beanfield War