LSLL: You have a long track record of using Texas history in fiction. What made you choose this most recent episode in The Big Drift?

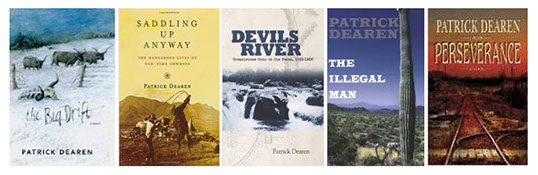

PATRICK DEAREN: Although my family roots in West Texas go back to the 1880s, it was only after I set out on a lore and legend quest in 1982 that I began to appreciate the region’s historical heritage. When I put on my novelist hat, I always look for some overlooked aspect of that history. For The Big Drift, I found it in the riveting accounts of the massive cattle drift of 1884–85, when a Great Plains blizzard pushed hundreds of thousands of open-range cattle south to the Pecos and Devils Rivers.

The Devils River, in particular, has been neglected in literary circles. I devoted several years to producing my nonfiction book Devils River: Treacherous Twin to the Pecos, 1535–1900, so I was familiar with the big drift’s effect on the Devils country. As many as 200,000 beeves piled up along the river, thereby necessitating the largest roundup in western annals. The cattle drift and its aftermath constituted an astounding event that offered great material for a novel.

How has your background as a journalist informed your career as a novelist?

I wouldn’t trade my experience as a newspaper reporter for anything. Not only did it help hone my style, but it provided ideas that led directly to a couple of my novels. This month, TCU Press will reissue (in ebook) a revised edition of my novel The Illegal Man. Originally published in 1981, this novel grew out of a ten-part newspaper series on illegal immigration that I wrote for the San Angelo Standard-Times.

The Illegal Man is the story of a Mexican national who, desperate to provide for his family, enters the U.S. illegally and finds work on a West Texas ranch. The prototype for my main character was an actual illegal alien I interviewed on a Glasscock County ranch. Throughout this work, I literally wove fiction from fact, and when I tell of my main character’s dramatic entry into the U.S., I describe an actual Rio Grande crossing point where I watched border patrolmen capture illegal aliens.

You grew up in Sterling City, Texas, a town of about 1,000. How did that influence you as a writer?

Sterling City has grown a bit since those days; it had only 700 residents when I was in high school. I’m a huge fan of small towns, where everyone is an individual and there’s a citywide sense of family.

In regard to writing, probably the most important development came in 1966 when my high school English teacher, Bob Bass, suggested that I consider writing as a career. Little did he realize that he had created a monster. I went home that very afternoon and began my first novel—at age fourteen. If I hadn’t grown up in Sterling City and attended Sterling High School, I may never have discovered writing.

Which Texas authors inspired your work, and which active Texas writers do you admire?

At age ten, I discovered Edgar Rice Burroughs, whose novels I admired so greatly that it’s a little surprising that I needed a teacher’s encouragement four years later to inspire me to write. Burroughs remains my favorite author, with Leigh Brackett a close second, which explains why three of my twelve novels have been science fiction.

Neither Burroughs nor Brackett had Texas connections, but there are certainly Texas writers I look up to. In the nonfiction realm, I’ve always enjoyed the works of J. Frank Dobie (the master storyteller) and J. Evetts Haley (the master stylist). In fiction, the late Elmer Kelton achieved extraordinary things, and I particularly appreciate how, almost single-handedly, he elevated West Texas out of a literary wasteland.

In terms of active Texas writers, I think we can’t overlook some of the fine work produced under deadline pressure at newspapers. If you’ve never read Rick Smith in the San Angelo Standard-Times, you’ve missed out. I’ve appreciated Rick’s style ever since we worked together at the Standard-Times in the 1970s. He’s also an accomplished playwright.

As a highly prolific writer, do you have a special routine that results in such productivity? What is your writing process like?

I’ve never considered myself prolific. I guess I’ve brushed shoulders too often with authors such as Chet Cunningham (300+ books) and Robert J. Randisi (600+ books) to consider my output significant. Truth be told, I’m a painstakingly slow writer.

My routine varies, depending on whether my project is nonfiction or fiction. For nonfiction, I pile my files around my computer and peck away until I’ve exhausted my material. For my forthcoming Bitter Waters: The Pecos River’s Struggles—an environmental history of the Pecos—I spent five years researching and writing. The University of Oklahoma Press will publish Bitter Waters in 2016.

For my two most recent novels, The Big Drift and To Hell or the Pecos, I adopted what may be a unique method: I write in longhand during my daily 4-1/2-mile walks. I don’t merely make notes; I literally write on the go. I crafted The Big Drift over the course of 1,850 miles during 395 straight days. I even developed a new metric for writers: WPM, or words per mile. I find that I average 35 WPM.

How has publishing changed since you started? How are things different for you in the age of Amazon, e-books, print-on demand, and the like?

Exceptions exist, but most publishers will tell you that sales are down across the board. This is especially true in the westerns field. For university presses in the Southwest, the standard 2,000-copy print runs of a few years ago have dwindled to 500 or 750. Ebook sales make up part of the difference, but total sales are nevertheless a fraction of what they once were.

In face of declining sales, I do all that I can to broker the licensing of subsidiary rights such as large print. Center Point Large Print, which caters to libraries nationwide, brought out an attractive hardcover edition of To Hell or the Pecos in December, and its sales have already exceeded the total sales of the 2012 TCU Press first edition.

What advice would you give to aspiring historical novelists?

One word: persevere. I think perseverance is the key to success in almost everything, whether in writing or another occupation or in interpersonal relationships. It’s no accident that I titled my favorite novel Perseverance, the story of a young man’s journey along the rails in Depression-era Texas. I devoted 32 years to producing seventeen drafts before it was published in 2006.

In terms of historical fiction, I recommend that an aspiring novelist revolve deeply human stories around little-known events. Finding these events may require considerable research, which itself demands perseverance.

The Big Drift has been selected by the Academy of Western Artists for the 2014 Elmer Kelton Award. As someone who knew Elmer Kelton personally, what does this honor mean to you?

Elmer Kelton was more than a great writer; he was the essence of humility and kindness. He was a gentleman and a gentle man, as he once said of our mutual dear friend Paul Patterson. For all his achievements—seven Spur Awards, four Wranglers—Elmer Kelton’s most enduring accomplishment was how he conducted himself as a man. To receive an award bearing his name is one of the greatest honors I can imagine, as it represents qualities much more important than a literary endeavor.

I hear you play a mean ragtime piano. Does music play a role in your fiction?

Thus far, ragtime piano has played a role only in my novel Perseverance, the most personal of all my works. What ragtime does for me is provide an all-important diversion from my writing. All writers need some type of escape in order to recharge their batteries. For me, I find it in the syncopated strains of “Maple Leaf Rag” or in my solo backpack treks into Southwest wilderness areas.

So, here's the most important question: what's your quintessential Texas meal?

Some Texas natives might argue for barbecue or chicken fried steak, but for me there can be only one answer: beans and cornbread. It’s what I was raised on, and I still think there’s nothing better.