Michelle Newby is contributing editor at Lone Star Literary Life, reviewer for Foreword Reviews, freelance writer, member of the National Book Critics Circle, and blogger at www.TexasBookLover.com. Her reviews appear or are forthcoming in Pleiades Magazine, Rain Taxi, World Literature Today, South85 Journal, The Review Review, Concho River Review, Monkeybicycle, Mosaic Literary Magazine, Atticus Review, and The Collagist.

Michelle Newby is contributing editor at Lone Star Literary Life, reviewer for Foreword Reviews, freelance writer, member of the National Book Critics Circle, and blogger at www.TexasBookLover.com. Her reviews appear or are forthcoming in Pleiades Magazine, Rain Taxi, World Literature Today, South85 Journal, The Review Review, Concho River Review, Monkeybicycle, Mosaic Literary Magazine, Atticus Review, and The Collagist.

Lone Star Book Reviews

of Texas books appear weekly

at LoneStarLiterary.com

Ashley Hope Pérez grew up in Texas and served in the Teach for America Corps in a neighborhood similar to the one depicted in her debut novel, What Can't Wait. She has worked as a translator and is completing a PhD in comparative literature. She spends most of her time reading, writing, listening to audiobooks, and teaching college classes on vampire literature and Latin-American women writers. For fun, she bakes cookies and runs. She lives in Indiana with her husband, Arnulfo, and their son, Liam Miguel.

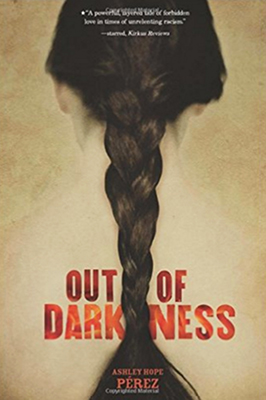

Ashley Hope Pérez

Carolrhoda Lab

Hardcover, 978-1467742023 (also available as an ebook), 408 pgs., $18.99

September 1, 2015

Henry Smith moves his children, twins Cari and Beto, along with his stepdaughter and their half-sister, Naomi, to New London, Texas, in 1936, where he works in the new booming oil industry. Henry is Anglo, Naomi is Mexican, and the twins are half-and-half. Naomi, hating Henry and blaming him for her mother’s death, doesn’t belong anywhere — the owner of the whites-only grocery (“No Negroes, Mexicans, or dogs” reads the sign in the window) won’t let her shop there and the owner of the grocery for blacks is nervous when she brings the twins, who pass for white. Naomi finds kindness, acceptance, and, eventually, love, with Wash Fuller, a black boy who does odd jobs for the school. Influenced by historical accounts of the 1937 explosion of the New London School, Ashley Hope Pérez uses the explosion to bring the conflicts to a shattering conclusion.

Out of Darkness is fine historical fiction. Pérez weaves separate narratives of each of the characters, including “The Gang,” the dispassionate report of a vicious collective Greek chorus of high school students, to create a devastating portrait of barriers — race, gender, religion, and class — in East Texas during the Great Depression.

Pérez’s characters are distinct, complex individuals. Henry, with his “born-again smile” and “wholesome look of the redeemed,” lives a life defined by selfishness and self-pity. Superstitious, he reunites with his children after several years and moves them to East Texas because his pastor told him that was what God wanted, but Naomi had always been “a shadow at the edges of his happiness. Later, she’d been a brief, disastrous solution.” Henry “Anglo-cizes” the children’s names, a move that doesn’t sit well with Naomi, who considers “Smith” “a slick, faceless thing, a coin worn smooth. Maybe that was why he [Henry] did not understand that carrying a name was a way of caring for those who’d given it. Naomi Consuelo Corona Vargas. That was her name.” Wash is smart and impatient with the necessary bowing and scraping to whites. “Wash knew better. … Better was a safe place. Better was what you were supposed to do. … But Wash…wanted to know Naomi more than he wanted to know better.”

Pérez uses precisely chosen words with multiple meanings to poetic effect. A reluctant Naomi is tempted to wait in Henry’s truck instead of joining the church picnic “away from the dressed-up chickens that would peck and peck at her until they found something tasty.” Beto loves the piney forests of East Texas, so different from his native San Antonio, because the “woods gave him the feeling of being inside and outside at the same time. Full of birds and animals but hushed, too, like a church the hour before Mass.”

The intricate plot develops gradually, but inexorably; the masterful pace moving us from vague unease, through trepidation, to horrified certainty. Out of Darkness is appropriately titled and the “heart rot” hollowing the tree that Naomi and Wash use as a hiding place is the perfect metaphor for the whole society.

* * * * *