I’ve written in a variety of genres simply because I have always loved reading all of them, from Milton to Gibbon to Frost to Faulkner.

Donald Mace Williams of Canyon is a true Renaissance man — or perhaps Anglo-Saxon or Texas frontiersman. His most recent novel, The Sparrow and the Hall is set in seventh-century Northumbria, but his impressive verse chapbook, "Wolfe", presents an adaptation of Beowulf set in 1890s West Texas. A former city editor of the Amarillo Globe-News who has taught at three universities (including journalism at Baylor and English at West Texas A&M) and worked for papers from the Fort Worth Star-Telegram to Newsday, Williams is our guest for a special Lone Star Listens interview for Labor Day weekend.

LONE STAR LITERARY LIFE: Don, tell us a bit about your background, especially in Texas, where you earned undergraduate and graduate degrees at our state’s universities.

DONALD MACE WILLIAMS: I was born in Abilene and had lived in four states before I was five years old. But my parents, both of them native Texans, kept coming back to Texas, as I did when I was grown. Apart from my dad’s restlessness, which I inherited, the family kept moving when I was small because somewhere, somewhere, there must be a job.

It was the time of the Great Depression, which I, since I was born on Black Thursday (October 24, 1929), obviously started. My parents, my older brother, and I lived in two big canvas tents for a couple of years, in first the Oregon woods and then the South Texas brush country, near Uvalde. We kids loved it, of course. So did our mother, if you can believe it, but my dad, out of duty to us and against his conservative principles, eventually took a job as an educational adviser with FDR’s Civilian Conservation Corps.

Many more moves then, in and out of Texas. When I was a newspaper reporter in Washington state and homesick for Texas, I found a job with the Amarillo Globe-News. There I met my wife-to-be, Nell Osborne, and more moves followed. I worked for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram and other newspapers for fifteen years with only two and a half years of college. Finally, in the hope that a college teaching job would give me more time to write fiction and poetry, I got two degrees in English from Texas Tech, then a Ph.D. from the University of Texas. Since I was forty-five by then and my doctorate was in Beowulfian prosody, I found no work in my academic field, taught journalism for seven years at three universities, including Baylor, then went back to newspaper work. My last job was as writing coach and weekly columnist for the Wichita Eagle. I retired in 1998, since when Nell and I have lived in Canyon.

You’ve both practiced and taught journalism, and you’ve written for papers large and small. What persuaded you to pursue a career in news?

My dad, who had been, among other things, a reporter in Dallas and Boston, was my inspiration. Besides, words had always interested me, and newspaper work seemed a way to use them for more or less a living. For most of my career, newspapers were still thriving. It was easy to get reporting and editing jobs, and I often found the work and the atmosphere exciting. Still, I really wanted to write things that might not vanish in a day. Partly because I had been a zealous student of classical singing since my late teens and spent a couple of hours every day vocalizing and studying music, and partly also because I was plain lazy, I couldn’t or didn’t find time for much “serious” writing. Nearly all of that has come since my retirement.

When did you know you wanted to be a writer?

I must have known somehow when, as a five-year-old, having been taught to read by my parents and brother, I wallowed in Robert Louis Stevenson’s A Child’s Garden of Verses and A. A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh. Next came The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, which I practically memorized, Mark Van Doren’s wonderful Anthology of World Poetry, and reams of mostly awful stuff, in pulp magazines and Big Little Books, about cowboys, frontier heroes, athletes, and such. I hope the trash eventually set me a helpful example of how not to write. But I don’t know that I wrote much outside of cute little themes for school until I was in my mid-teens, when I wrote a few poems and short-short stories, all of them fortunately lost. So to answer the question, I must have been in my early twenties before I wanted to write.

These days you’re retired in Canyon, Texas, where you’ve frequently hiked the trails of Palo Duro Canyon — an inspiration for some of your writing. What brought you to the Panhandle?

In 1955, I had been in California and Washington state for more than three years. My employer in Spokane, The Spokesman-Review, had sent me out to Moses Lake in the West Texas–like middle of Washington to cover five small towns in the Columbia Basin irrigation project. Though I reported all kinds of news, it wasn’t good experience for me. No city editor gave me assignments or told me how I should have written this story or that. I had no experience of the extremely valuable kind of newsroom comradeship that goes to coffee and tells jokes about dangling participles. And most of all, the settlers of the irrigation project were young veterans, their wives, and their young children. young children. In my eight or ten months in Moses Lake I did not meet one unmarried, uncommitted girl. That was what brought me to Amarillo, where I did indeed meet such a girl, the one to whom I have now been married for nearly sixty years. As for what brought me, and her, to Canyon after retirement, there were two main factors. First, we loved and missed the Panhandle. Second, Nell’s mother lived in Pampa, where we could see her often. We’ve lived in Canyon better than seventeen years now and have always been glad of our choice.

Aside from news stories, you write in numerous genres and styles — including fiction, nonfiction, and epic and lyric poetry. Your first full-length book, now available as Italian POWs and a Texas Church: The Murals of St. Mary’s (Texas Tech University Press, 2001), and your most recent, The Sparrow and the Hall: Love and Betrayal in Anglo-Saxon England (Bagwyn Books, 2015) are worlds apart! How have you mastered such a wide range?

I don’t know about mastery, but thanks. I guess I’ve written in a variety of genres simply because I have always loved reading all of them, from Milton to Gibbon to Frost to Faulkner. In my writing, with ideas coming less and less often these days, I have taken up translation, especially of Rilke’s poems. That way, I don’t have to have ideas—Mr. Rilke supplies them for me, and all I have to do is fall in love with one poem after another and have each of them in turn sit for its sound-portrait. Maybe I’ll still have an idea of my own once in a while, too. We’ll see.

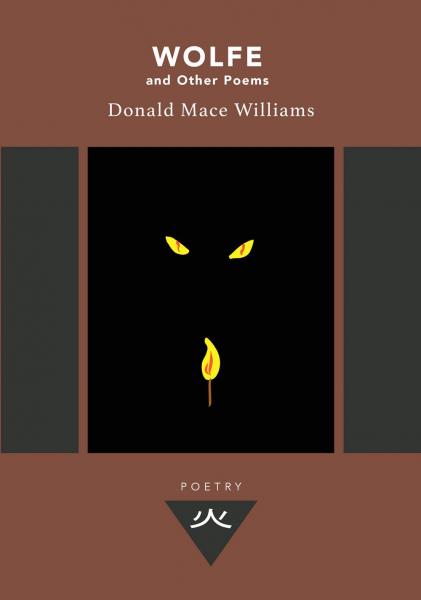

Your epic poem, Wolfe, takes an ancient tale and sets it in the Texas Panhandle. What inspired you to recreate the hero Beowulf as the 19th-century cowboy Billy Wolfe?

Ignorance, to tell you the truth. Although I wrote my dissertation at UT on the prosody of Beowulf, I never felt that I fully understood or appreciated the poem. Beowulf’s heroism never moved me until the last episode, when he was old and nonetheless took on the fiery dragon. Maybe, I told myself, if I could imagine a more or less plausible, more or less modern recasting of the story, I could then think back 1,400 years, reinstating the substitutions, and come closer to the intended empathy.

I had long been struck by the daring of certain cowboys on the XIT Ranch who crawled into lobo wolves’ dens with a pistol in one hand and a candle in the other and fired when they saw the occupants’ eyes glowing in the light. (J. Evetts Haley tells about the wolfers in The XIT Ranch of Texas.) Since the new story needed a touch of the supernatural, I took care not to identify the cattle-raiding, man-killing monsters in “Wolfe” but only to suggest that they might be uncanny re-emergences of a long-extinct superwolf that had lived in those parts. It was fun writing “Wolfe.” And I’m still not sure I appreciate Beowulf.

I wrote The Sparrow and the Hall for somewhat the same reason I wrote “Wolfe.” I wanted to get a feel for life on a small farm in Anglo-Saxon times. So I read for more than a year, spent a week on site in Northumbria to get close to the terrain and the weather, and then, in the writing, imagined how rural and small-town West Texas people would have acted back then and over there. The central character, Edgar, is in fact loosely patterned on my wife’s late brother, Jim Osborne, who farmed near Panhandle. Writers who find rejection discouraging, by the way, might like to know that Bagwyn Books was the seventy-sixth publisher I had tried with The Sparrow. If Bagwyn hadn’t taken it, I was going to quit trying.

Which Texas writers have influenced you as reader and writer?

One was the man I named above, Haley. Both the XIT book and his biography of Charles Goodnight carried me along with their enthusiasm, though I doubted that Goodnight was as benign a character as Haley would have had us believe. I’d like to say that Stephen Harrigan, with The Gates of the Alamo, influenced my writing of The Sparrow, but the fact is that I had finished that manuscript before I read Harrigan’s powerful novel. No doubt Larry McMurtry’s characters and dialogue, at least those of his first two or three books, got favorably stuck in my mind and ear, and I imagine his later efforts, especially Lonesome Dove, influenced me negatively, as in Don’t, for heaven’s sake, write like that. Elroy Bode’s buffed straightforwardness has to have affected me as a writer. The prose of A. G. Mojtabai impresses me as something unattainably (by me) subtle and precise. And my late friend Richard Phelan, in his book Texas Wild and especially in his many letters and e-mails to me, showed a keen critical faculty, a delightful wit, and a fastidious simplicity. Since coming to Canyon I have also read and admired the work of several Texas poets, including William Wenthe, Larry Thomas, Wendy Barker, and Catharine Savage Brosman.

What do you feel is the role of form in poetry today?

Modern poets keep saying that their work, far from being mere prose set off in lines, actually has form and musicality. I keep trying to understand, but really, I have to agree with Frost about playing tennis without a net. The trouble is, not many professors and editors think as I do. I write almost exclusively in meter and often in rhyme, and I find that only a few stout hangers-on among editors of literary magazines will readily look at what I submit. Sorry, I guess, but I grew up on real form, real musicality, as in Keats, Goethe, Dickinson, Frost. As for the role of formal poetry today, I have to say it’s minimal and will get more so as fewer people grow up on the masters. And civilization will have sunk another few inches into the muck.

Print journalism has changed drastically in the past decade, with digital content, online delivery, citizen journalism and blogs. (This publication, for instance, was “born digital” in 2015 and reaches readers via website and email.) What’s the future of the newspaper industry, as you see it?

I suspect that real newspapers, printed on paper, will hang around as long as the muscles of people my age and maybe my children’s ages remember the acts of unfolding, spreading, and reading. But the surviving papers will also have strong presences online, as many of them already do. Those will be less and less like newspapers of sixty years ago. Graphics and photographs—often “shopped”—will keep on shouldering words aside. Fewer and fewer reporters and editors will write well and read critically. Fewer subscribers will know the difference.

And yet, can’t we hope that some readers of discrimination will always demand quality in newspapers, so that a few big papers will be able to keep going? Those would have to cover large circulation areas, maybe the whole country, the way the Wall Street Journal does. But what will come of stories about drug arrests on I-40? Where will the obits go? I persist in thinking of such matters as reported in black type on white paper. Wishful thinking, and wistful, I know. For the most part, I’m afraid paper papers are going the way of rhyme and meter.

Last question, for our Labor Day weekend. You’re an outdoors enthusiast, familiar with Texas and the West. What’s one destination you believe no visitor to Texas should miss?

I thought of Palo Duro Canyon, of the Big Bend, and even of ordinary ranch country on the High Plains, which I love. But no. Nothing in Texas can really approach the springtime display of flowers, especially bluebonnets, in a large part of the state, from northeast of Tyler to southwest of Kerrville. I doubt that any other state has flower scenery to match.

* * * * *

An excerpt from Donald Mace Williams’s "Wolfe"

Tha com of more under misthleoþum

Grendel gongan, Godes yrre bær. —Beowulf

When he arrived at the cave or den, the hunter took a short candle in one hand, his six-shooter in the other, wiggled into the den, and shot … by the reflection of the light in her eyes. —J. Evetts Haley, The XIT Ranch of Texas

Fat Herefords grazed on rich brown grass.

Tom Rogers watched three winters pass,

Then, all his ranch paid off, designed

A bunkhouse, biggest of its kind

In that wide stretch of Caprock lands,

To house the army of top hands

That rising markets and good rain

Forced and allowed him to maintain.

At night sometimes a cowboy sang

Briefly to a guitar’s soft twang

While others talked, wrote letters home,

Or stared into brown-bottle foam.

Rogers, white-haired as washed gyp rock,

Stood winding Cyclops, the tall clock,

One night and heard the sleepy sound

Of song across the strip of ground

Between the bunkhouse and the house.

He smiled and dropped his hand. Near Taos,

At night, pensive and wandering out

From camp, a young surveyor-scout,

He had heard singing just that thin

Rise from the pueblo. Go on in,

A voice kept saying, but he stood,

One arm hooked round a cottonwood

For strength until, ashamed, he whirled

And strode back to the measured world.

Strange, how that wild sound in the night

Had drawn him, who was hired to sight

Down lines that tamed. So now, he thought,

Winding until the spring came taut,

This clock, this house, these wide fenced plains,

These little towns prove up our pains.

He went to bed, blew out the light

On the nightstand, said a good night

To Elsa, and dropped off to sleep

Hearing a last faint twang.

From deep

In the fierce breaks came a reply,

A drawn-out keening, pitched as high

And savage as if cowboy songs,

To strange, sharp ears, summed up all wrongs

Done to the wilderness by men,

Fences, and cows. With bared teeth then,

Ears back, the apparition skulked

Across the ridges toward the bulked,

Repulsive forms of house and shed,

Till now not neared. The next dawn’s red

Revealed a redder scene. The pen

Where calving heifers were brought in

In case of need lay strewn and gory,

Each throat and belly slashed, a story

Of rage, not hunger; nothing gone

But one calf’s liver. His face drawn,

Rogers bent close to find a track

In the hard dirt. Then he drew back,

Aghast. Though it was mild and fair,

He would always thereafter swear

There hung above that broad paw print

With two deep claw holes a mere hint,

The sheerest wisp, of steam. He stood

Silent. When finally he could,

He said, “Well, I guess we all know

What done this. No plain lobo, though.

I’ve seen a few. They never killed

More than to get their belly filled.

This one’s a devil. Look at that.”

DONALD MACE WILLIAMS is a former writing coach for The Wichita Eagle and reporter and editor for papers that include Newsday, the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, and the Amarillo Globe-News. He has taught English and journalism at West Texas State and Baylor Universities. Williams holds a doctorate in English from the University of Texas. He lives in Canyon, Texas, and his poetry has been published widely in journals in the U.S. He is the author of Interlude in Umbarger: Italian POWs and a Texas Church, and the novels Black Tuesday's Child and The Sparrow and the Hall. His epic poem "Wolfe" and his memoir Being Ninety were published as a single edition in February 2023.