Each week Lone Star Literary profiles a newsmaker in Texas books and letters, including authors, booksellers, publishers.

Kay Ellington has worked in management for a variety of media companies, including Gannett, Cox Communications, Knight-Ridder, and the New York Times Regional Group, from Texas to New York to California to the Southeast and back again to Texas. She is the coauthor, with Barbara Brannon, of the Texas novels The Paragraph RanchA Wedding at the Paragraph Ranch.

Kay Ellington has worked in management for a variety of media companies, including Gannett, Cox Communications, Knight-Ridder, and the New York Times Regional Group, from Texas to New York to California to the Southeast and back again to Texas. She is the coauthor, with Barbara Brannon, of the Texas novels The Paragraph RanchA Wedding at the Paragraph Ranch.

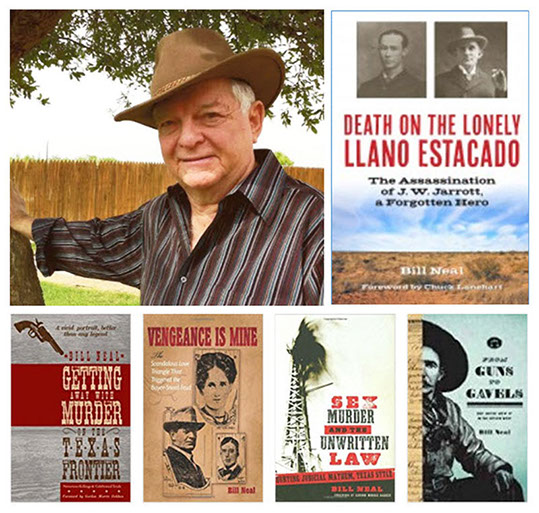

Bill Neal practiced criminal law in West Texas for forty years: twenty as a prosecutor and twenty as a defense attorney. He is the author of Getting Away with Murder on the Texas Frontier: Notorious Killings and Celebrated Trials (named Book of the Year for 2008 by the National Association for Outlaw and Lawmen History, received the Rupert N. Richardson Award for the best book on West Texas history from the West Texas Historical Association, and named a finalist for both the Violet Crown Award by the Writers’ League of Texas and the Spur Award by the Western Writers of America); From Guns to Gavels: How Justice Grew Up in the Outlaw West, and Sex, Murder, and the Unwritten Law: Courting Judicial Mayhem, Texas Style. Neal and his wife, Gayla, live in Abilene.

9.24.2017 Abilene author Bill Neal on journalism, mentors, and “making history something someone would want to read"

Texas attorney and author Bill Neal knows the law — and he knows how to spin a tale. He has combined his skill in observation of fact with a keen knowledge of Texas history and an ear for the telling detail, to publish some of the most fascinating accounts of frontier law and life in print. When you ask Bill a question, you’d better sit down for the answer, because he’ll take the long way around. But it’ll sure be worth the trip.

LONE STAR LITERARY LIFE: Congratulations on the publication of yet another rousing book about Texas justice, Bill. Let’s start by discussing the basics: where were you born, and where did you grow up?

BILL NEAL: I was born January 31, 1936, in the small West Texas town of Quanah—county seat of Hardeman County. (The town of Quanah, by the way, is named for the Comanche Indian chief Quanah Parker.) That’s located just eight miles south of the Red River—the northern boundary of Texas and southern boundary of Oklahoma and just around the Southeast corner of the Texas Panhandle. I grew up on a ranch owned by my grandfather, Will Neal, and my dad, Overton “Boots” Neal. An only child, I grew up on that remote ranch along the Pease River breaks.

How do you think that upbringing influenced your writing?

Growing up in a rural West Texas ranching community, I had no thought of ever becoming an author or a lawyer. Granddad and dad were cowboys, and that’s what I thought I would become. (There were no authors or lawyers in my background on either side of my ancestors.)

The rural West Texas ranching background did influence my writing later, since all my books are nonfiction describing real people and events in frontier West Texas, western Oklahoma, and eastern New Mexico. Consequently, I knew the land, the pioneers that settled there, and the way they thought, spoke, and acted.

You’re an attorney and an author. Which came first, and how do the two professions complement each other?

The answer to this question is rather complex.

In the spring of 1958 when I was in the infantry officers basic training camp at Fort Benning, Georgia, I received an issue of the weekly Quanah Tribune-Chief newspaper. The front-page headline startled me, and it triggered a 180-degree change in my life and my professional aspirations. The headline read: “The Famous Neal Ranch Sold.”

When I returned to my hometown of Quanah after the summer of 1958, I didn’t have a home or an occupation. I did, however, have a friend named Carroll Koch, who owned the Tribune-Chief, and she said that since the year 1958 was the centennial celebration of the establishment of our county (Hardeman County) that she wanted to publish an extra edition of the Tribune-Chief recording history of the county and its beginning, including all prominent families, businesses, churches, schools, etc., etc. and she didn’t have the time or staff to research and write the history so why didn’t I undertake that assignment. After all I didn’t have anything else to do.

I accepted, and soon became totally involved in and challenged by that assignment. The more research I did, the more I realized how much more needed to be done. Several years later, I returned to this task in my spare time and that resulted in my first book titled: The Last Frontier: The History of Hardeman County.

In the meantime, however, I had “accidentally” gotten a taste of journalism. Before my army service I had attended Hardin-Simmons University and was majoring in economics. But I got acquainted with a professor who taught journalism, and so signed up for a course. I liked it, so I took a couple more journalism courses and wound up—during my senior year—being editor of the college student newspaper, The Brand. There I met a man who really stimulated my interest in writing. A. C. Greene was an Abilene native and at that time, a reporter for the daily Abilene Reporter-News. However, Hardin-Simmons hired him part time to teach a journalism course and also supervise the publication of The Brand. A. C. and I became close friends and remained so for the rest of his life. He later moved to Dallas and wrote a book column for the Dallas Times-Herald and began writing books — including my favorite nonfiction book, A Personal Country, about growing up in Abilene and that portion of West Texas. A. C. wrote the forewords for a couple of my local history books.

I collected family stories told to me by the descendants of the original pioneer settlers of the little community (now a ghost town) named Medicine Mound. Our Stories: Legend of the Mounds: The Medicine Mound Settlers’ Community Scrapbook was published in 1997.

The University of North Texas Press has published two of my last nonfiction books, including my latest, just out in July 2017 as a part of its A. C. Greene Series, Death on the Lonely Llano Estacado: The Assassination of J. W. Jarrott, A Forgotten Hero.

Meanwhile, after completing my history of Hardeman County research, I got a job as a reporter for the Abilene Reporter-News and then the Amarillo Daily-News as a general news reporter — plus, during my Amarillo stint I was also named book editor for the Sunday Amarillo paper.

(Pause here for a sidebar tale. Fred Post was the managing editor of the Amarillo Daily News. He was a tall, imposing man of few words — reminded me of General Patton. Anyway, I had a brief conversation with him when he hired me. So I went to work. Didn’t hear anything from Fred for about a year. Then one day I got a note that Fred Post wanted to see me. Oh, my God, I thought, what the hell have I done? Is he gonna chew me out for something? Is he gonna fire me? I went to his office door and looked through the glass. He was sitting behind his desk. Nobody else in his office. I cautiously knocked on the door. He looked up. Nodded for me to enter. I entered, then sat down in a chair across the desk from him. He was shuffling papers. Didn’t say a word for a spell. Then he looked up and said this: “Neal, I want you to handle the Sunday book review page.” And then he resumed shuffling papers on his desk. I sat there stunned but very quiet. I thought, well, I reckon he’s gonna give me some instructions about what he wants me to do about the Sunday book review page. But he said nothing.

At that time the prominent, wealthy, and very conservative Whittenburg family owned the Amarillo and Lubbock daily newspapers. Shortly before I was hired as a reporter, Amarillo Daily News reporter Al Dewlen had written a book titled The Bone Pickers. It was listed as a novel — nonfiction. But, in truth, it was a very thinly veiled satire on the proud and mighty Whittenburg family. Dewlen resigned his job as a reporter for the Daily News, correctly anticipating the wrath his treatise would ignite in the Whittenburg clan.

Now, back to my encounter with Fred Post. I sat there in my chair after being designated by him as the new book editor. Sat there quietly for about ten minutes, Fred still shuffling papers and jotting down notes. Finally, I concluded that he wasn’t going to give me any instructions as to how he wanted the book page. (Plus, there was no mention of me being relieved of any duties as a news reporter. And no mention of any raise in my salary.) So I concluded Fred was through with me. I got up and started to leave his office. But just as I was about to open his office door to leave, he looked up at me and said this, in a very commanding tone:

“Neal,” he said, “Let me tell you this: I’d better never, ever see one f—ing word on that book page about the g_________d Bone Pickers.”

“No sir,” I said, and then departed. I never reviewed that book for the Sunday book page.

By the fall of 1961, I had decided I wanted to make a change: I wanted to have an occupation that would allow me to be my own boss and to make a better salary than a newspaper reporter. Hence, in the fall of 1961 I enrolled in the University of Texas law school in Austin. But I didn’t lose my ambition to write, and in my senior year at UT I was named comment editor of the University of Texas Law Review. In the spring of 1964 I graduated as Grand Chancellor of my class and was offered a one-year position as a briefing attorney for the Texas Supreme Court. After that I was offered positions with several large Texas law firms but turned them down because I wanted to be my own boss and this country boy was not about to live in a big city.

So I returned to my hometown of Quanah and practiced with a local lawyer and close friend, Lark Bell. Two years later I ran for and was elected as district attorney over a multi-county district—the 46th Judicial District—Hardeman, Foard, and Wilbarger counties. I served eight years as district attorney of that district and later three terms as district attorney for the 50th Judicial District—Baylor, Knox, Cottle, and King counties. I retired from law practice in 2004 having served twenty years as a district attorney and another nineteen as a private practitioner doing mostly criminal defense work.

During those thirty-nine years practicing law in small West Texas counties I learned much, not only about criminal law practice, but also about many events which had occurred in the vast area of West Texas that had never received much attention in newspapers, television, or books. Many were criminal cases that had never been solved, or even if so, there was much more to the cases that hadn’t been printed or received media coverage. And so I saw that there were many more fascinating true stories that could be told and which included facts and twists that had never been revealed to the public. I began researching and writing. Death on the Lonely Llano Estacado is my sixth such book, all published by university presses. The title of the first one tells much about the content of all six: Getting Away with Murder on the Texas Frontier: Notorious Killings and Celebrated Murder Trials.

What was your first big break as an author?

Several years before I retired from active law practice I began writing drafts of various tales that begged to be told. I had no instructions on writing or marketing such books. I just sat down and started telling a story, but I soon realized that they needed considerable “polishing up” before submitting them to any university press.

One day — I believe in 2002 — when I was a prosecutor for the 50th Judicial District which included the little town of Benjamin in Knox County, State Photographer of Texas Wyman Meinzer came to my office and wanted help with a copyrght infringement matter. He and I became friends, and I told him of my ambition to find a university publisher for my stories. Wyman was well acquainted with Judith Keeling, editor of Texas Tech University Press, and put me in touch with her. She saw my drafts, helped me select and arrange the material, and published my first book.

Once with the submission of another manuscript to a university press editor, I ran into an apparent roadblock. The editor, before accepting my manuscript, had to follow its standard procedure of submitting a proposed manuscript to three anonymous experts for approval. Two of those voted thumbs-up on my manuscript. But the third refused at first, saying that while my story was very interesting and would appeal to many readers, my “informal” writing style was “beneath the dignity of a university press.”

I aimed to tell a documented non-fiction western story, but it was not submitted as a scholarly treatise or thesis. And I cited a quote from noted historian and best-selling author David McCullough: “No harm is done to history by making it something that someone would want to read.” I went on to say that I attempted to be a good and documented story teller, and avoided long boring sentences burdened by scholarly jargon or by the legalese of an appellate court brief. Finally, I won approval of the editor.

As you mentioned, you have a new book, Death on the Lonely Llano Estacado. Would you tell our readers about the book and its inspiration?

A friend of mine, fellow criminal lawyer Chuck Lanehart of Lubbock, is also interested in western history—particularly in frontier crimes. Chuck had written an article for the criminal defense bar magazine, Voice for the Defense, about the unsolved assassination of J. W. Jarrott, who had been assassinated back in 1902. The murder had never been solved. I talked with Chuck about the story and the possibilities of possible further investigations, and he said with his busy practice, he didn’t have time to devote to more research. I asked him if he would object if I took over the task—with his help and advice and due credit therefor. Chuck said he’d welcome it. And so it began.

As it turned out, the assassination of Jarrott was the result of a range war on the South Plains of Texas between the big cattle ranchers and the “intruding” small family settlers. No one had ever been tried for the Jarrott murder that had happened 115 years ago.

Researching it and finding a factual basis for the name of the assassin and the man who had hired the assassin was quite a task. But with Chuck’s help I finally fit together the pieces of the puzzle. And that’s documented in the book.

Your books deal with Western history and law and order. Did you read a lot of Western titles growing up? What kinds of books/authors did you enjoy reading?

Mark Twain was—and is—my favorite author. I also like the fiction stories of Elmore Leonard, several of which are the basis for some Hollywood films. I have always been fascinated by Civil War stories, biographies, and autobiographies of famous people, outlaws and lawmen as well as others.

I like western nonfiction authors such as Sallie Reynolds Matthews, Frederick Nolan, Leon Metz, Bill O’Neal, Chuck Parsons, J. Evetts Haley, Walter Prescott Webb, J. Frank Dobie, Glenn Shirley, John Miller Morris, and others.

You live in Abilene, a city with a great literary heritage. What, in your view, makes Abilene such a great place for readers and writers?

Abilene is a good town for writers. We have three main colleges with research-rich libraries. We also have a really good fall book festival that attracts many area authors as well as book enthusiasts from a large area of small towns. Since I was editor of my college student newspaper and first met and became friends with A. C. Greene here in Abilene, and since I worked as a reporter for the Abilene-Reporter News, I consider it an especially good place to live.

You’ve turned out a lot of books in recent years. What’s your creative process like?

My creative process is usually kicked off when I discover a tale with great potential—one that has never received much publicity. As pointed out above, I practiced law for thirty-nine years, and during that time my practice took me to many small towns in West Texas. Frequently, I came across stories — sometimes fragmented stories of lawmen and outlaws, of crimes and trials, etc., and I would think: “You know, there has to be a lot more to this story than this little tidbit.” My curiosity would be piqued. I couldn’t stop mulling it over in my mind, so I would begin my research down that cold trail.

What advice would you give to aspiring authors?

This advice is for writers of nonfiction books, or for novels based on real incidents. The advice is this: research, research, research. Then write a draft. Then research, research, research. Then rewrite, rewrite, rewrite. Then maybe even more research.

Researching can become addictive, and you will probably feel that part of the work is never going to end. I have often started down the researching trail of some historical quest but that trail almost always has a trail with many forks in the road. It often raises more questions than answers. So you can spend forever searching down those dusty side trails of the past.

I know one devoted Western history buff who has been chasing rabbits down all those old trails for years but has never actually written a book. Sometimes you just have to go with what you have. My experience as a newspaper reporter taught me that at some point in time, you just “gotta let go” and go with what you got. One time I discovered a very important fact several years after I had concluded a story in a previous book. It was so important that I used it as the basis for a subsequent book.

What’s next for Bill Neal?

I am beginning my memoirs. It will be stories of unrelated incidents that have occurred in the last eighty-one years. Some are funny, some are sad, some are just clinging to the borderline of the unbelievable. Some titles so far include: “The Time I Prosecuted a Victimless Crime,” “The Looser the Fit, the Tighter the Noose,” “A Cotton Patch Memory,” and “Let There Be Light.” This last story is about a day in 1948 — when I was twelve years old — when the electricity poles finally reached our remote ranch house.

* * * * *

Praise for Bill Neal’s VENGEANCE IS MINE

“ . . .[A] fascinating circuit-ride through a legal system [that] still displays flashes of its checkered past.”

—Dallas Morning News

“Bill’s vast experience as an attorney brings this story of love and revenge and murder trials to a new level. It is his portrayal of the legal strategy and of the flamboyant lawyers that brings a new dimension to this book. Bill is a gifted storyteller, as he has proven in his three previous books, and he is at his best in Vengeance Is Mine.” —Bill O’Neal, author of The Johnson-Sims Feud (UNT Press) and The Johnson County War

“Neal makes excellent use of court records, family correspondence, and newspapers in telling a tale that today sounds like a mix of Dateline NBC and Dallas, except that everyone knew who shot Colonel Boyce and his son.” —Western Writers of America Roundup Magazine

The Boyce-Sneed feud originated from a typical love story, but developed into a truth-is-stranger-than-fiction saga. Important aspects of the feud’s history are unbelievable. Bold-faced, cold-blooded murders; trumped-up criminal charges; disappearing witnesses; surprising courtroom procedures; twisted Texas law; unusual insane asylum lockups; and an enraged, mean-spirited husband make the story seem more like the plot of a dime novel than the real thing. In Vengeance Is Mine, Bill Neal, a retired attorney, tells the incredible yarn well and compellingly.”

—New Mexico Historical Review

“Bill Neal has done his usual painstaking research into the voluminous files of newspaper and trial records that trailed this strange and exotic tale over half a century.”

—Southwestern Historical Quarterly

“Neal has us understand that in Texas, as most of the Old South, there is the written law and then there is the unwritten law, the latter wherein a man has the right to protect his home and family. Of course, one might ask, was Beal Sneed protecting his home or his reputation?”

—Wild West History Association Journal

“[A] story that would be any screenwriter's dream . . . . Vengeance Is Mine will appeal to armchair historians, those interested in slightly more esoteric aspects of Texas history, and those looking for a good, exciting read about a scandal and its ripple effects.” —Review of Texas Books

* * * * *