Michelle Newby is contributing editor at Lone Star Literary Life, reviewer for Foreword Reviews, freelance writer, member of the National Book Critics Circle, and blogger at www.TexasBookLover.com. Her reviews appear or are forthcoming in Pleiades Magazine, Rain Taxi, World Literature Today, South85 Journal, The Review Review, Concho River Review, Monkeybicycle, Mosaic Literary Magazine, Atticus Review, and The Collagist.

Michelle Newby is contributing editor at Lone Star Literary Life, reviewer for Foreword Reviews, freelance writer, member of the National Book Critics Circle, and blogger at www.TexasBookLover.com. Her reviews appear or are forthcoming in Pleiades Magazine, Rain Taxi, World Literature Today, South85 Journal, The Review Review, Concho River Review, Monkeybicycle, Mosaic Literary Magazine, Atticus Review, and The Collagist.

Lone Star Book Reviews

of Texas books appear weekly

at LoneStarLiterary.com

In addition to The Book of Wanderings, Kimberly Meyer’s nonfiction work appears in The Best American Travel Writing 2012, Ploughshares, The Kenyon Review, Ecotone, The Oxford American, The Georgia Review, Agni, The Southern Review, Brain,Child, Crab Orchard Review, Natural Bridge, and Third Coast, and her audio-documentary work has been featured on Public Radio International’s “This American Life.”

Her writing has been supported by residency fellowships to the Bread Loaf Writer’s Conference and the Vermont Studio Center, has been awarded a Houston Arts Alliance Established Artist Grant, an Inprint/Michener Fellowship, and a Brown Foundation Fellowship, and has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize.

A Ph.D. graduate of the University of Houston’s Creative Writing Program, Meyer currently teaches in the Great Books program in the Honors College at the University of Houston and lives in that thriving, multicultural city of no zoning with her husband and three daughters.

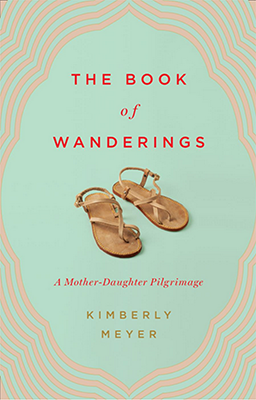

KIMBERLY MEYER

The Book of Wanderings:

A Mother-Daughter Pilgrimage

New York: Little, Brown

Hardcover, 978-0-316-25121-1 (also available as ebook and audiobook)

368 pages, $27.00

March 24, 2015

The Book of Wanderings: A Mother-Daughter Pilgrimage by Houston professor Kimberly Meyer is equal parts memoir, travelogue, philosophical treatise, and love letter to her firstborn daughter, Ellie. Meyer yearned for a “bohemian-explorer-intellectual kind of life” but became pregnant in her senior year of college. After Ellie is born, Meyer attends grad school, marries, and gives birth to two more daughters. She sets aside youthful ambitions until she comes across The Book of the Wanderings of Brother Felix Fabri in the Holy Land, Arabia, and Egypt during dissertation research, a discovery that reawakens those earlier dreams.

Meyer and eighteen-year-old Ellie embark on a trip following Father Fabri’s footsteps: beginning in Ulm, Germany, proceeding south through Italy to Greece, across the Mediterranean to Israel and the Palestinian Territories, then south again into the Sinai desert, arriving two months later in Cairo. The juxtaposition between Fabri’s pilgrimage and the author’s reminds us that not much has changed in five hundred years. People still plunge into the Jordan River fully clothed. Bedouins still keep watch over flocks of sheep. Monks still walk the Via Dolorosa.

Meyer ably contrasts the mundane frustrations of travel—language confusion, unfamiliar food, unreliable transportation—and the transcendent moments when you make that ineffable connection with those who came before you, “swallowed up…in…the sweep of historical time.” There is elegant imagery: “When Mohammad Atwa Musa knocked on the door to retrieve me, all the women, as one, deftly lifted their veils to cover themselves, the movement like the taking flight of a flock of birds.” And vivid description: “Scattered across the undulating azure waves are Chinese junks, Indian dhows, European galleys and caravels. On land, in the spaces between the rivers and the place-names and the mountains, rise walled cities with their golden crenellated towers and minarets and onion domes and Gothic spires. In the deserts: conical tents, carmine and emerald and sapphire, their flaps open to the sirocco winds.”

With self-deprecating humor and gentle irony, Meyer describes their travels, attempts peace with dread of the rapidly approaching empty nest, and searches for spiritual solace that has always eluded her, struggling to balance the push of “pure possibility” and the pull of the familiar. But during the trip she’s conflicted and feels unmoored. “What did I want? To be essential to other human beings or to be free…? These were mutually exclusive options, even if we were pretending with this trip that I could have both.”

Confronting Sartre’s “God-shaped hole” in modern Western life, The Book of Wanderings contemplates the existential. Is home a particular place, person, or thing, or is it within us? Do we find ourselves there or when we leave? Is the search for objective truth futile? “We exist. We don’t know why. We die. We don’t know what follows. We love. What we love will leave us. We suffer though we have tried to be good. These aren’t questions and they don’t have answers.”

* * * * *